Accidents

April 29, 2013

John Aubrey’s autobiography is one of the longer and more disorganised entries in his ‘Brief Lives’ manuscripts. Aubrey changes between past, present and conditional tenses, and between the first- and third-person throughout. He begins by accounting for his life in ‘an astrological respect’, and goes on to describe his parentage, birth, education and career, financial fortunes, and other affairs, often giving insight into personal dispositions and inclinations. As a child, for example, Aubrey wished he lived in Bristol, where he would have access to ‘watchmakers, locksmiths etc’. ‘At 8, I was a kind of engineer’. Endearingly, Aubrey writes of himself: ‘His chief virtue: gratitude’.

Several pages in, Aubrey begins a new heading, ‘Accidents of John Aubrey’, which covers a range of occasional, unexpected events including his father’s death, and his own broken engagement in 1666, a year when ‘all my affairs ran kim kam’. As well as these incidents, the section also includes accidents as we would now define them, as an unfortunate and unforeseen physical incident. A list of dated entries describe Aubrey’s memories of falling off his horse, falling over or suddenly being taken ill:

1655: (I think) 14 June, I had a fall at Epsom, and broke one of my ribs and was afraid it might cause aposthumation

[…]

1659 March or April, like to break my neck in Ely minster

One of the entries, recounting a narrow escape from being stabbed by a drunk stranger, seems to imply that Aubrey was attempting to set his accidents in the context of some astrological arrangement, as he adds a note: ‘(Memorandum: horoscope thus)’. The passage gravely concludes: ‘I have been twice in danger of drowning’.

In an article on ‘Editing Aubrey’, Kate Bennett describes Aubrey’s ‘Brief Lives’ manuscripts as ‘not [as] a closed literary text in the making’, but a ‘survey and map of the areas to be explored’. Bennett suggests that Aubrey’s brief autobiography, amongst the other biographies, is a work-in-process, asking questions of its own content: her (forthcoming) edition of Aubrey’s manuscripts is ‘intended to present the text as a process or project, rather than as a series of steps towards a closed, completed biographical moment’. A page of one of Aubrey’s manuscripts, showing his sketches, corrections, and on the upper right-hand-side, a partly completed horoscope, has been reprinted by Bennett (click on the image for a clearer picture):

(In Bray at al, eds, p.282, image taken from a British Library handout from here)

Accidents also features in Samuel Jeake’s diary. Jeake, a Nonconformist merchant and amateur astrologer from Rye in Sussex, kept a record of his life which he plotted against the constellations. He back-dated his diary to his own birth, and the first entry of July 1652, when he was four months old, records how ‘I fell out of bed but had no hurt’. Like Aubrey, Jeake recorded accidents and other important events of his life up to the time he embarked on the diary: in 1660, when he was eight, or ‘About this year (but I remember not exactly) as I was catching of Crabs at full Sea; I fell from a Rock into the Tide up to the middle’.

As the diary unfolds more detail is given with the memory of each accident, or near-accident. On 16 August 1693, coming home in the dark, ‘I was in great danger of falling over a Load of Wood which lay out in the Middlestreet, which being just in my way, I was within Two steps of stumbling on it, not seeing it. But it pleased God to send a Flash of that Lightning which was very frequent that evening’. On 30 September, Jeake was again going home in the dark, this time on horseback. Riding downhill along ‘a Rivulet of water’, Jeake’s saddle slipped forward onto the horse’s neck, and ‘I was twice like to be thrown off into the water’ – if this had happened, Jeake speculates, he might have been drowned, or ‘trod underfoot’ by his horse, ‘or at least have been all wet’.

A similar near-accident on 10 January 1683 resulted in Jeake catching his feet in his own stirrups. ‘The Sun at the time of this Accident was in the 15th degree of Aquarius which is supposed to signify the legs’, he notes. Almost (but not quite) falling out of bed in January 1693, Jeake is also put in mind of the astrological context: ‘I would therefore refer the accident to the opposition of Mercury out of an airy sign’.

Elsewhere, Jeake made a horoscope which includes an impressive list of 202 unpredicted injuries. As Michael Hunter and Annabel Gregory have written in the introduction to their edition of the diary, ‘one of Jeake’s motives in compiling the diary was to subject the events of his life to astrological analysis’; he was trying ‘to refine the techniques and test the principles of astrology by careful empiricism’. Horoscopes Jeake made for himself, similar in form to those Aubrey made for himself and his other subjects (though Jeake’s are tidier), are reprinted in the Hunter/Gregory edition, as shown on the dust-jacket:

.

(Cover Hunter and Gregory, eds, image from here)

The experience of traffic accidents, dangerous illnesses, broken bones and embarrassing falls are things that remain for a long time in human memories. Aubrey’s and Jeake’s autobiographical writings seem to show a particular interest in the memory of what we would now call ‘accidents’ – though they would have defined this word more broadly, as any occasional or chance event. In particular, Jeake and Aubrey set these ‘accidents’, or disordered events, against the constellations, which they believe to be orderly but inscrutable. By recording their lives, both Aubrey and Jeake seem to have been trying to assess a correspondence between very real events on earth: horses falling over in mud, men tumbling into rivers – and movements in the sky above the earth. Each man, stores up a memory, and seems to attempt to reveal a pattern in a series of otherwise random collisions.

.

* John Aubrey, Brief Lives, Woodbridge: Boydell 1982-98, ‘John Aubrey’ pp.7-15

* Kate Bennett, ‘Editing Aubrey’, in Ma(r)king the Text: The presentation of Meaning on the literary page, Joe Bray, Miriam Handley & Anne C.Henry, eds., Aldershot: Ashgate 2000, pp. 271-290

* Samuel Jeake, An Astrological Diary of the Seventeenth-Century: Samuel Jeake of Rye, 1652-99, eds., Michael Hunter and Annabel Gregory, Oxford: Clarendon Press 1988

Travel and visual memory

September 3, 2012

‘I don’t travel with a camera. My holiday becomes the snapshots and anything I forget to record is lost’, says the protagonist of Alex Garland’s 1990s backpacker novel The Beach, which Danny Boyle made into a film starring Leonardo DiCaprio and, weirdly, Tilda Swinton. The Beach was a blockbuster, both as a book and as a film, partly because it represented an increasingly popular experience: relatively affluent young men and women from England travelling ‘gap year’ itineraries through South-east Asia.

Garland’s statement about photographs is something of a commonplace now, at the end of the summer holidays, in 2012 – the idea that the holiday album can replace the memory of the holiday. The holiday and the memory of the holiday are counterpointed, or triangulated, in Garland’s imagination, against visual capture.

Seventeenth-century understandings of visual representation have been given a great deal of critical attention over the past two decades. In the introduction to Artful Science: Enlightenment, Entertainment and the Eclipse of Visual Education, Barbara Maria Stafford argues that ‘visual education’ ‘arose in the early modern period’:

Significantly, it developed on the boundaries between art and technology, game and experiment, image and speech. The exchange of information was simultaneously creative and playful. We need, therefore, to get beyond the artificial dichotomy presently entrenched in our society between higher cognitive function and the supposed merely physical manufacture of ‘pretty pictures’. In the integrated (not just interdisciplinary) research of the future, the traditional fields studying the development and techniques of representation will have to merge with the ongoing enquiry into visualization. In light of the present electronic upheaval, the historical understanding of images must form part of a continuum looking at the production, function and meaning of every kind of design. [p.xxv]

It was common, in late seventeenth-century England, for relatively affluent young gentlemen of a certain disposition to take themselves off on an educational foreign tour, keeping, usually, to conventional itineraries. When Edward Browne, aged 24, was travelling in Europe in 1668-9, he sent many things home: a box full of different kinds of metal ore, several notebooks, a diary, copied-out letters; a book of dried plants from the physic garden at Padua, and probably much else too. He sent most of these things to his father, Thomas Browne, in Norwich, and other things to the Royal Society in London. Edward Browne also bought back at least two picture albums, now held in the British Library (Additional manuscripts 5233 and 5234). Unfortunately, copyright and image charges mean I can’t reproduce them here. Captions and verbal descriptions will have to give a sense of Browne’s collection.

The opening pages contain a series of black and white engravings and watercolours of Turkey and Persia. They show desert landscapes, markets, camps, riders, and, on folio 13, ‘The curing of ye colicke by ye Persians by treading on their Bellies, & ye hubble bubble or Instrumt thro which they smoke Tobacco’.

Browne also has a picture of a jasper waterbutt owned by a hairdresser in Cairo. A Sultan’s crown with ‘Oestridge egges’ dangling off it with the apostles’ faces drawn on them. A Moorish palace with moors and jesters looking out of the windows. Portraits of gypsies in their costumes. What looks like a placid cow, but turns out to be a gilded bull: ‘Among the many odde curiosities in the City of Nurnburg I observd a bull of wood and guilded and set in the Shambles’. There are several town views and pictures of bridges and aqueducts. (Browne was especially interested in bridges, and in the back of a different journal he had made a list of ‘famous bridges I have seen’ – all the famous London bridges, the bridge in Bristol, Pont Neuf in Paris – and so on.)

In the middle of the book, looking a bit out of place, is ‘John Higgins born at Wolsall in Staffordshire’ – Higgins, most likely an acrobat, is shown doing ‘his several postures’.

There are pictures of different kinds of boats, with captions: ‘In these boats live whole families’. There is a diagram sent from Lisbon of the late eruption at Tenerife, and a representation of an enormous pillar, which is done as one very long projecting arm, cut out (perhaps a couple of centimetres wide) and folded into the book – when you fold it out, it reaches about a metre or so beyond the album.

When Browne got home he published his Travels in two different books of 1673 and 1677. The books were successful, and the two were published together in a more lavish synoptic edition of 1685. This edition had more pictures in it, most of which had been engraved from the originals in Browne’s albums. In the preface to the new edition, Browne declines to describe these new pictures, because a ‘Particular Description’ in the preface ‘would prevent the satisfaction of considering [these objects] in their proper places; to which I shall refer you, wishing you the same pleasure in viewing them there, that I have had formerly in beholding them in their due Situations, and in the Contemplation and Description of them afterwards’ (Browne 1685, sig.Ar).

There is an interesting analogy between the real object, in its ‘due situation’ – things as they are seen in their native environments – and ‘viewing them’ as they are visually represented in the book. These two things are counterpointed, or triangulated, in Browne’s imagination, against verbal description, which would ‘prevent the satisfaction’ of visual experience in the ‘proper places’. In his mind, at least as he describes it here, visual memory is analogous to real experience, and it is in writing that places are displaced in our minds. I am sure Browne’s picture collections would be worth further study.

–

* British Library Additional Manuscript 5233,4

* Edward Browne, A Brief Account of Some Travels in Hungaria, Austria, Styria, Servia, Bulgaria, Carinthia, Macedonia, Carniola., Thessaly and Friuli, London: Benjamin Tooke at St Paul’s, 1673

* An Account of Several Travels Through a great part of Germany, London: For Benjamin Tooke at the sign of the Ship, 1677

* A brief account of some travels in divers parts of Europe viz Hungaria, Servia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Thessaly, Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, and Friuli : through a great part of Germany, and the Low-Countries : through Marca Trevisana, and Lombardy on both sides of the Po, London: For Benjamin Tooke at the sign of the Ship, 1685

* Alex Garland, The Beach, London: Penguin 1996

* Barbara Maria Stafford, Artful Science: Enlightenment, Entertainment and the Eclipse of Visual Education, Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1994

Historical commute

January 13, 2012

The walk to the Archives de l’État on the Rue du Chéra in Liège takes you above the huge, new Guillemins railway station which opened in 2009. The vast structure of glass, steel and white concrete was designed by Santiago Calatrava to be open on both sides, allowing you to exit onto a verge leading uphill to grander houses with views, or downhill to shabbier suburbs.

Photo by Joao Carlos, taken from http://www.wallpaper.com

Photo by Joao Carlos, taken from http://www.wallpaper.com

Calatrava’s work is famous, admired by some and disliked by others: his streamlined, skeletal buildings include the Zurich Law Library and the Valencia City of Arts and Sciences. Liège-Guillemins station is a key interchange: on the high-speed rail network that can take you all round Belgium, to Germany, Paris or – on the Eurostar – to the UK: all of the platforms are designed for rapid arrival and departure. A document produced by the Belgian State Railway (who commissioned the station, through which it is estimated 33,000 people pass through every day) states that ‘with a majestic station symbolising its development, Liège is moving forwards’, and a British press article ran with the title ‘Liège-Guillemins train station: a ticket to tomorrow’. Expensive, travel-related architecture is necessarily about a faster future, and about where one might go from the departure station. At the end of the working day the station seems busier than Paris Nord or St Pancras.

But if one uses Guillemins to commute to the archives on Rue du Chéra the station does seem to take you deeper down into Liège as well as through it — it is built on the site of an old convent set up by followers of St Guillaume, and the details of this order are kept up the hill above the station in the record office along with the archives of Spa, a nearby municipality and ancient watering-place that gave its name to the whole genre of spas, and indeed the ubiquitous mineral water brand Spa drunk by most commuters in this region.

Spa Ville archival folder, holding records of C17 Spa

The museum at Spa holds vessels in which mineral water was bottled in the seventeenth century, and is well worth a visit, not far from the Spa station opposite which is a vast building owned by and bearing the Spa Monopole logo. Like the Liège station with its Guillemite history expanded, the Spa station is overlooked by a logo of the mineral water brand.

* http://www.liegeonline.be/en/medias/pdf/gareguilleminsEN.pdf

Red Herrings

November 2, 2011

Online resources like the Oxford English Dictionary, the Dictionary of National Biography or Early English Books Online allow scholars, in the twenty-first century, to follow lines of enquiry without actually going to the library, which is a mixed blessing. Some things get lost when accessing early modern books online– marginalia, say, or Copernican hairs – and there are lots of ways in which these very useful internet resources can swallow time.

*

In 1685 the Royal Society summarised a French advertisement for an engine that neutralised burning and cooking odours

composed of severall hoops of hammered Iron of about 4 or 5 Inches diameter, which shutt one into the other: it stands upright on the middle of the Room, upon a sort of trevet [trivet] made on purpose.

The engine was tested with ‘the most fetid things’: ‘Coal soakt in cats piss, which stinks abominably’; ‘encense’, and ‘red Herrings’ (RS Classified Papers 3i f.65). Hooke was evidently using the phrase ‘red herring’ in a taxonomic rather than a figurative sense – he referred to it as a recognisable environmental pollutant.

The engine passed the test, neutralising the smell of the coal, incense and herrings, and dispersing the smoke so that ‘the most curious eye’ could not ‘discover’ it, ‘[n]or the nicest nose smell it’.

There is a recipe for red herrings in Kenelm Digby’s 1669 Closet, or Excellent Directions for Cookery, which promises to satisfy ‘the curiosities of the Nicest palate’. (Digby’s cookery, the preface says, is so excellent, there ‘needs no Rhetoricating Floscules to set it off’.)

Digby got his recipe for ‘Red Herrings broyled’ from Lord d’Aubigny – probably Charles Stewart, who was the eleventh and last Stewart Lord of Aubigny – his line was extinguished when he drowned aged 33, without an heir, in 1672 at Helsinger, better known to early-modern scholars as Elsinore.

The Oxford English Dictionary characterises a red herring, like a kipper, by its method of preparation: sense 1b. ‘A herring that has been dried and smoked’. The OED doesn’t list this literal red herring as obsolete or even archaic, but the most recent citations come from history books (the red herring as a bar snack in Georgian Glasgow and a delicacy in Rembrandt’s Holland respectively). My local fishmonger told me with some certainty that they’re not available any more. A red herring, he said, isn’t an actual fish.

The phrase is usually used today in a figurative sense, as ‘a clue or piece of information which is or is intended to be misleading, or is a distraction from the real question’ (OED sense 2). This meaning dates from the nineteenth century, but it derives from an older practice wherein hunters would deliberately trail red herrings, or other stinking things, to draw on their hounds. It seems that the practice, which was probably Medieval in origin, was still a common use for red herrings in the seventeenth century – Nicholas Cox explains ‘what a Train-scent is’ in his Gentleman’s Recreation of 1686:

the trailing or dragging of a dead Cat, or Fox, (and in case of Necessity a Red-Herring) three or four Miles, (according to the Will of the Rider, or the Directions given him) and then laying the Dogs on the scent.

*

Using searchable online resources, several red herrings could be traced in different, now-defunct contexts – as an experimental subject, as a food, as a hunting accessory. But these fish were real as well as figurative. Digby’s recipe gave practical instructions on how to recreate the authentic early modern smell that Hooke had been working at eradicating:

My Lord d’ Aubigny eats Red-herrings thus broiled. After they are opened and prepared for the Gridiron, soak them (both sides) in Oyl and Vinegar beaten together in pretty quantity in a little Dish. Then broil them, till they are hot through, but not dry. Then soak them again in the same Liquor as before, and broil them a second time. You may soak and broil them again a third time; but twice may serve. They will be then very short and crisp and savoury. Lay them upon your Sallet, and you may also put upon it, the Oyl and Vinegar, you soaked the Herrings in.

Inside inns

March 29, 2011

Richard Ames’ The Search after Claret; or a Visitation of the Vintners (1691) takes the reader on a pub-crawl around London in search of a glass of the Bordeaux wine, or as Ames sometimes specifically refers to a glass of Pontac: the family name of the owners of the Haut-Brion estate.

In his Grands Vins, Clive Coates explains that the Pontac dynasty was founded at the turn of the sixteenth century by Arnaud de Pontac, and that the Haut-Brion vineyards were consolidated from bundles of land by his son Jean, who lived to be 101. Each successive son became a premier président of the hereditary Bordeaux parlement, and, after the Restoration, a representative of the family came to London to promote the family’s produce and to open The Pontac’s Head, alleged to be a fashionable dining spot. But in 1689, when England joined the Grand Alliance — the European coalition against Louis XIV’s France — French import channels to England were closed down, stopping the flow of Claret in London pubs and therefore sending Ames on his satirical search. Numerous publications from the Company of Vintners throughout this period enable the historical charting of the sanctions and their opposition.

The pub-crawl, which starts at Whitechapel, lasts two days, and is filled with unsatisfactory drinks, empty glasses and everywhere the news that stocks of French wine were dry. The text is fun for its sense of atmosphere, including invocations of certain bartenders and landlords and signs. Everywhere on the men’s journey they encounter and exchange brief words with other drinkers:

XXI

At his Door with a Rummer we found Neddy Dr______ner,

And perceiv’d by his looks that he was a Complainer.

We whisper’d in’s Ear, and desir’d (could he spare it)

To let us have a Bottle or two of old Claret;

He started as frightened to hear our Demands,

And answer’d, why Gentlemen (holding up’s Hands)

D’ye know what you mean? Let me die like an Ass,

If this twelve-month I’ve seen, smelt, or tasted a Glass.

XXII

We shook our Heads at him, and crossing the way,

At the Globe we attempted another Essay;

When askt for old Claret, the Drawers were inchanted,

And we for our parts thought the Mansion was Haunted,

So leaving the Tavern in study profound,

We concluded indeed that the Globe was turn’d round,

XXIII

At the Mitre we call’d in, and walking the Entry,

Spy’d a Soldier in Habit much unlike a Centry,

Who spewing, did in his short intervals say,

Pox take your Red Port, and so Reel’d on his way,

We soon took the hint from his Stomach’s Alarms;

They’re wise gain Experience by other Mans Harms.

All manner of different traditions of drinking are linked to the various inns. The Mitre in Aldgate is where ‘young married couples to make their hearts lighter / Take a jolly brisk Glass to embolden ’em to say / That very hard chapter, for ever and for aye’. Peacocks at St Paul’s is surrounded by a bustle of drapers and chair-makers ‘whereof some are Christians, and others are Quakers’. The last bunch of drinkers they encounter, on the second day, is easy to picture:

XXXV

The last Tavern we came to, was that of the Rose;

At the Door of which stood such a parcel of Beaus,

Who in Eating and Drinking great Criticks commence,

And are Judges of every thing else but of Sense,

When we saw ’em make Faces and heard one or two Swear,

That the Wine was the Devil they lately drank there;

We rely’d on their word, and ne’re stept o’re the Groundsil,

But thought they spoke truth like General Council.

The two-day search is at once acutely local and international, as the inn-crawlers obtain news from a variety of London drinkers about whether various hostelries contain produce from Bordeaux. Politics intersects with drink in a text where the insides of inns and conversations with exasperated drunks reflect the state of England’s international relations.

*Clive Coates, Grands Vins (University of California Press, 1995), 311-3.

C A R N I V A L E S Q U E

January 24, 2011

A selection of fine early modern posts to kick-start 2011.

Over at Three Pipe Problem Hasan Niyazi compares Giorgione’s ‘Tempest’ to the work of fellow Venetian artist Carpaccio. This post, which pieces together knowledge about the symbolism of different birds, shows how Twitter-based collaboration can unite independent researchers across the globe to striking effect. Emily Brand at Shire Histories writes about human male plumage and seventeenth-century opinion about male wigs, while LOL Manuscripts! addresses the phenomenon of birds falling from the sky with characteristic vim.

Mercurius Politicus tells a great story of Henry Walker hurling his pamphlet To Your Tents, O Israel into Charles I’s carriage in 1642. The interesting thing about this post is that no copies of the pamphlet survive, so its historical content seems to become the very act of it being thrown. If it had hit him in the face he might have required a sixteenth-century nose job, as described by Writing the Renaissance.

Executed Today features Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch of a hanged man and links it to computer game Assasin’s Creed II, and The Chirurgeon’s Apprentice writes about the seventeenth-century condition of syphilophobia. Over at Fragments we are reminded that music was not the food of love for Thomas Overbury, who was allegedly sent ‘tarts and jellies laced with poison’ via a musician. The great ‘O’ antiphons from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer are discussed over at Chantblog, The Renaissance Mathematicus offers a complex and rewarding post on Kepler and The Conveyor’s smart blog features an illustrated post on Martin Lister’s copperplates.

Frederik de Wit’s beautiful, newly digitised Dutch town atlas is showcased over at BibliOdyssey, and In Pursuit of History draws our attention (and supplies some fabulous illustrations) to a number of interesting posts about frost fairs. Streets of Salem features some fascinatingly illustrated trade cards, a portion of which are early modern, and for those of you wanting to read about love in advance of Valentines Day, Room 26 Cabinet of Curiosities has posted a readable copy of The seamans doleful farewel or, The Greenwitch lovers mournful departure. A meeting of a different kind – between two men on their way to be killed – is described by Early Modern Whale.

Early Modern Carnivalesque Jan 2011

January 3, 2011

Airs, Waters, Places will host an Early Modern Carnivalesque on 24 January. Please send your nominations of great Early Modern blog posts to me airs waters places at gmail dot com (no spaces), or post them in the comments below by 21 January. Thanks!

Logging in The Tempest

December 28, 2010

Last Christmas day – 2009 – our boiler broke and we had to fill several Holy sacks, to keep the house warm while it was snowing outside.

Caliban has other uses for a log, suggesting some ways for Stephano to murder Prospero, including ‘with a log / Batter his skull’.

In the precedent scene, Ferdinand has the same weapon for an unusual prop, when he enters ‘bearing a log’. Prospero has given him an impossible commission But rather than roll a massive rock up a hill or find the golden fleece, defeat a giant or locate treasure, Prospero has a task that is more appropriate to his location, and would be recognisable to many seventeenth-century theatregoers – Ferdinand has to fetch in the logs:

I must remove

Some thousands of these logs and pile them up,

Upon a sore injunction

It’s an endless task on a mythic scale, but it is also a humble job, and not appropriate to Ferdinand’s estate:

I am in my condition

A prince, Miranda; I do think, a king;

I would, not so!–and would no more endure

This wooden slavery than to suffer

The flesh-fly blow my mouth.

Only for Miranda’s sake, he says, ‘Am I this patient log-man’. She for her part wishes the climate would intervene in sympathy with her pity…

I would the lightning had

Burnt up those logs that you are enjoin’d to pile!

…and predicts that the logs will join her by weeping tears of resin:

Pray, set it down and rest you: when this burns,

‘Twill weep for having wearied you.

She even, after watching him for a time, offers to replace him:

If you’ll sit down,

I’ll bear your logs the while: pray, give me that;

I’ll carry it to the pile.

Ferdinand refuses her offer – his job’s not appropriate for her, either:

I had rather crack my sinews, break my back,

Than you should such dishonour undergo,

While I sit lazy by.

The scene ends with their marriage-pledge to one another.

I wonder why carrying logs was the right task, and whether Prospero used them for heating or for something else, and if this scene has anything to say about seventeenth-century timber – whether it belongs in a fairy-tale prince-disguised-as-a-woodcutter tradition, or if knowledge about the collection, transport, trade, regulation and use of wood can be useful or interesting when we read it.

Rereading The Tempest, I’ve been struck by the detail in Shakespeare’s descriptions of the nature of the island – its trees, nuts and berries; birds and bird’s nests; fish and crustacea; cave, rock and shore; freshets and pools; as well as the human and non-human personae, and the character who is neither one nor another, but an indistinguishable ‘thing’ in between.

Glass story

December 15, 2010

In The Invention of Comfort, John E. Crowley writes that:

The English word story, for a horizontal division of a building, derived from the Middle English term storye, which came from the Latin historia and referred to the story told by a horizontal series of illustrations on glazed windows. (p.42)

Crowley illustrates this with a great example from Chaucer’s The Book of the Duchess. William Camden mentions something similar in his description of Peterborough abbey (later Cathedral): ‘The forefront carieth a majesty with it, and the Cloisters are very large, in the glasse-windowes whereof is represented the history of Wolpher the founder, with the succession of the Abbots’ (p.513). Painted glass windows were often smashed by iconoclasts, but breaking windows in general could be part of persecution, as one bad priest does to his host in Foxe’s Actes and monuments:

This dronken priest sitting at supper, was so dronke that he coulde not tell what he did, or els feyned himselfe so dronke of purpose, the better to accomplishe hys intended mischiefe. So it followed that this wretch, after hys first sleep, rose out of his bed and brake all the glasse windowes in his chamber, threwe downe the stone, and rent all his hostes bookes that he founde. (p.893)

This malefactor destroys the frames of his victims stories and exposes him to the elements — something windows are supposed to block while allowing agreeable illumination. In essence, he destroys his victim’s reading environment as well as directly destroying his books.

Glass windows were part of the scientific imagination. In his Anatomical Exercitations William Harvey used the skills of a private detective to prove that chickens broke out of their shells when they hatched, as opposed to the shells being broken inwards by the mother bird:

And as when Glass-Windowes are broken, a man may easily discover whether they were burst from within, or without; if he do but take the paines to compare the bent and inclination of the fragments remaining: So also when the egge is pierced, by the erection of the splinters all along the circuit of the Coronet, it is manifest that the invasion came from within. (p.130)

As part of his researches into air, and as an extension of experiments already undertaken with small animals in airtight glass containers, Robert Boyle imagined a set of windows looking inward on the story of human asphyxiation:

I have also had thoughts of trying whether it be not practicable, to make a Receiver, though not of Glass, yet with little Glass windows, so placed, that one may freely look into it, capacious enough to hold a Man, who may observe several things, both touching Respiration, and divers other matters; and who, in case of fainting, may, by giving a sign of his weakness, be immediately reliev’d, by having Air let in upon him. (p.192)

As far as I know, Boyle never made this contraption, but it is interesting to follow his imagination of viewing a human specimen gesturing for air through a series of little glass panes.

*John E. Crowley, The Invention of Comfort: Sensibilities and Design in Early Modern Britain (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001)

*William Camden, Britain (1637)

*John Foxe, Actes and monuments of matters most speciall and memorable (1563)

*William Harvey, Anatomical exercitations concerning the generation of living creatures (1653)

*Robert Boyle, New experiments physico-mechanicall, touching the spring of the air (1660)

Natural moralities

December 4, 2010

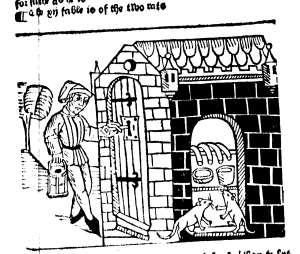

This perplexing image is from Caxton’s 1484 English edition of Aesop’s Fables, which at that point was not considered primarily a text for children. It depicts a rat, which is tied to the foot of a frog, getting carried off by a kite. As it is described in the text:

Now it be so / that as the rat wente in pylgremage / he came by a Ryuer / and demaunded helpe of a frogge for to passe / and go ouer the water / And thenne the frogge bound the rats foote to her foote / and thus swymed vnto the myddes ouer the Ryuer / And as they were there the frogge stood stylle / to thende that the rat shold be drowned / And in the meane whyle came a kyte vpon them / and bothe bare them with hym / This fable made Esope for a symplytude whiche is prouffitable to many folkes / For he that thynketh euylle ageynst good / the euylle whiche he thynketh shall ones fall vpon hym self

What is really going on in this fable? What is the moral system of each character? On a first reading it looks as though the rat and the frog are bound up in anthropomorphic co-operation and backstabbing, while the kite exists in another order of natural processes and inevitability. The kite is certainly not evil by intent. The frog has thought about visiting evil – for which I think we can read misfortune – on the rat and so is in turn rendered a victim. It is all in the titles: this is the fable of the rat and the frog, but it makes way for another form of incidental agency embodied in the figure of the bird who simply acts on the basis of normal predatory instincts. I don’t think the kite is meting out punishment in a considered manner here.

Even more intriguing are the fables where a human takes the kite role to become the natural hazard in a moral balance between two non-humans. Like for example the fable of the two rats.

In this fable a fat rat leads a poor rat into a human cellar containing plenty of food. While they are enjoying the food they are disturbed by a butler, who doesn’t see them but the encounter scares them and indicates hazard. The message is ‘Better worthe is to lyue in pouerte surely / than to lyue rychely beyng euer in daunger’, the kite-like danger here represented by a man who is out of the moral sphere and features as an accident or condition, just going about his normal job with no will at all towards the rats.

Aesop’s fables are interesting in this way because, although their lens is highly anthropomorphic, they offer up scenarios which include this third character outside the main moral transaction, and it is especially interesting when that character is homo sapein.